If you have a rare disease, the search for a diagnosis can often feel like the longest detective investigation – with no clues, lots of blind alleys and, occasionally, disbelieving authorities. It may seem like things are going nowhere, even for years.

Sometimes this is because information on the condition just isn’t available and not enough research has been done; other times it’s difficult to find someone knowledgeable enough to spot the signs of a rare disease. After all, these diseases are so rare that many doctors have never come across them in their careers. Either way, a person with a rare disease can end up playing investigator in their own personal medical mystery – and in some situations even end up solving the case, or devising treatment, for themselves!

Seven-year-old Alex’s family in Australia went through years of misdiagnosis after they realised that their young son had an intellectual disability and couldn’t speak. Doctors were unable to pinpoint what was wrong, so the family spent years looking for clues and vital information to help them.

One day their attention was drawn to a chance social media post concerning another child with similar symptoms who had Nicolaides-Baraitser syndrome (NCBRS). Alex’s mother said, “We found remarkable similarities, and it prompted me to start researching the symptoms. There was amazing resemblance between Alex and some of the other children.” It was the vital clue they needed to complete their search for the answers.

Being taken seriously, or even ‘believed’, is part of the challenge for many people with rare diseases, because their disease may not be obviously categorised or recognised. In some cases, they rely simply on a handful of ‘symptoms’ with seemingly no connection to each other. Joining those dots is the skill of the medical professional, but with over 6000 rare diseases in the world it’s not easy to have the information at your fingertips, especially when there is not much of it. All too frequently a diagnosis relies on a random chance meeting with someone, often somewhere far away, who is able to help solve the puzzle.

Leanne from Australia was passed from specialist to specialist after suffering joint pain, with some suggesting it could be psychosomatic. A chance meeting with someone at a pain clinic led to an initial diagnosis, after which she was taken more seriously and given scans which revealed torn ligaments and bones out of joint. Leanne said, “One of the surgeons admitted he had only seen an injury like mine from a high impact motorcycle accident. Yet I had done nothing traumatic. I didn’t even play sport!” Eventually, she was given a diagnosis of ‘Ehlers Danlos Syndrome’, but it came twenty years after her first symptoms.

Although it’s a relief for people to get a diagnosis, unfortunately thousands still continue to wait to find out exactly what is wrong with them, so they can get some kind of treatment or respite from their condition. And it’s not easy to be positive or plan a future when you don’t know exactly what you’re dealing with. It is the unsolved mystery; the one that needs to continually be taken off the shelf to see if any new information has come to light, or if there’s a new and better method of diagnosis that can help.

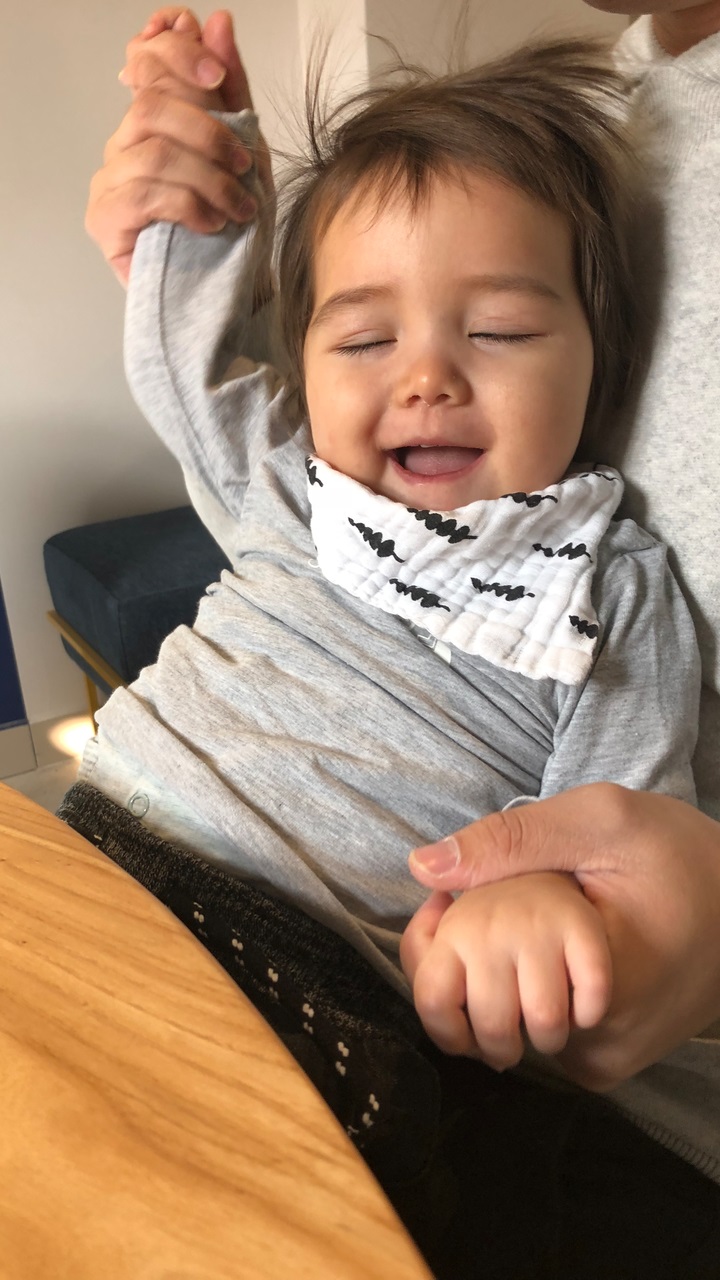

Baby Zayden’s mother is one of those still waiting. She knew something was wrong when her son was born. A tiny flicker in his eyes, the fact he didn’t seem to be growing properly, and the feeling he simply wasn’t ‘giving anything back’. She’s still waiting to find out what’s wrong. It’s been two years and despite Zayden having test after test, and consultation after consultation, with different doctors, no one has been able to pinpoint what his condition is. His parents have learned to cope, but “He fights against his muscles constantly,” says his mother. “Sometimes he has better days than others. Sometimes he can eat, other times it’s too hard. Sometimes he can smile, other times it’s too hard. We still hope for answers but until then we will continue to believe that no diagnosis means no limits.”

Perseverance and stamina are required of all those who find themselves with a rare disease. This can help them find a diagnosis which will eventually lead to a treatment or a way of being able to live with their condition.